Legal

How State Lawmakers Regulated Marijuana, Hemp, and Kratom in 2025

February 5, 2026 | Kerrie Zabala, Michael Greene

Key Takeaways:

Last week, the Wisconsin Supreme Court provided us with a golden opportunity to return to one of our favorite topics: Wisconsin’s Magic Veto Pen. All 50 states grant their governors the ability to veto bills passed by the legislature. Many state constitutions go even further by allowing governors to veto only specific portions of legislative language without vetoing the entire bill itself (called the “partial veto”). But no other state provides its governor with a partial veto as powerful as Wisconsin.

Wisconsin’s constitution, thanks to a 1930 constitutional amendment, allows the governor’s partial veto to encroach on the legislature’s lawmaking responsibilities. That amendment allowed appropriation bills to be “approved in whole or in part by the governor, and the part approved shall become law.” This, predictably, led to some shenanigans. For example, Governor Tommy Thompson (R) transformed a property tax credit into a school tax credit in 1987.

This practice of turning the state's budget process into absurd exercises in blackout poetry, deleting large sections of legislative language but leaving in parts of words and numbers to create brand new policy, grew too much for voters. They amended the state constitution in 1990 to prohibit governors from creating new words by deleting individual letters and again in 2008 to prevent governors from creating new sentences by combining parts of two or more sentences.

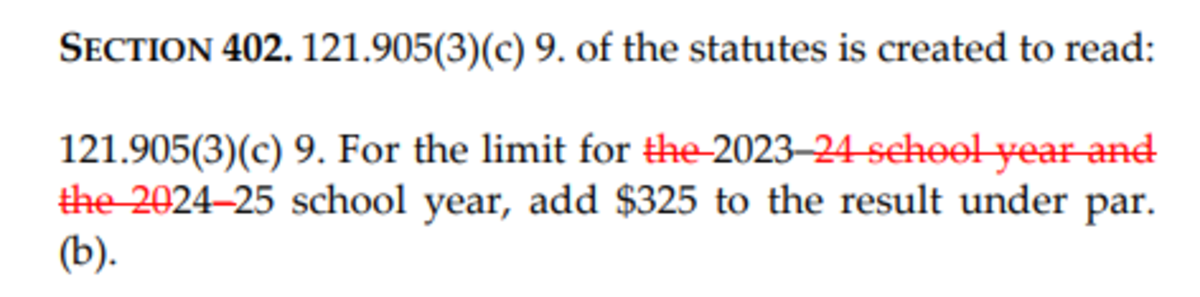

In 2023, Wisconsin Governor Evers (D) used the state’s unique partial veto to extend a school funding provision in the budget by 400 years. Evers took a line from the budget bill that would have extended a school funding program for the “2023-24” and “2024-25” school years and simply crossed out the “20” and the hyphen to create a year “2425” end date.

The legislature filed a lawsuit arguing that Gov. Evers’ veto violates the 1990 constitutional amendment that restricted the governor’s ability to strike individual letters to make new words. The governor’s office countered that his 400-year school funding veto struck individual numbers, not letters. The Court bought it.

Last week, the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s liberal wing, in a 4-3 decision, allowed the veto to stand. As the majority of the Court explained, “these partial vetoes, which struck only words and numbers, satisfy the requirements of [the state constitution]. There are no instances of the governor striking letters to make new words, or combining portions of sentences to create new sentences.”

The three conservative justices on the Court strongly disagreed with the majority’s opinion, writing, “The decision today cannot be justified under any reasonable reading of the Wisconsin Constitution.” The dissenting justices facetiously sketch out “how a bill becomes a law” under the majority opinion: “The legislature passes a bill in both houses and sends it to the governor. The governor then takes the collection of letters, numbers, and punctuation marks he receives from the legislature, crosses out whatever he pleases, and — presto! — out comes a new law never considered or passed by the legislature at all. And there you have it — a governor who can propose and enact law all on his own.”

The Wisconsin Supreme Court’s decision means that it's ultimately up to the voters again to decide whether to continue to rein in the broad partial veto power they gave the governor back in 1930. Be on the lookout for an upcoming ballot measure in the Badger State.

This article appeared in our Morning MultiState newsletter on April 22, 2025. For more timely insights like this, be sure to sign up for our Morning MultiState weekly morning tipsheet. We created Morning MultiState with state government affairs professionals in mind — sign up to receive the latest from our experts in your inbox every Tuesday morning. Click here to sign up.

February 5, 2026 | Kerrie Zabala, Michael Greene

February 4, 2026 | Sandy Dornsife

January 26, 2026 | Jason Phillips, Anthony Amatucci