State Government Affairs, Elections & Campaigns

How Lieutenant Governors Are Selected (And Why It Matters)

December 10, 2025 | Bill Kramer

September 2, 2025 | Bill Kramer

Key Takeaways:

As anyone following politics today knows, Texas recently enacted a rare mid-decade redistricting effort, causing California to respond, and now we might see several mid-decade redistrictings in Missouri, Florida, Ohio, and New York as well. Typically, a state will only draw congressional and state legislative district lines once per decade after the decennial census numbers are released and apportionment takes place. This was the norm throughout the 20th century. However, mid-decade redistricting was a fairly common occurrence back in the 1800s, especially after a political party flipped a state legislative majority. There are many excellent resources about today’s redistricting drama, but today I’d like to focus on a little history around mid-decade redistricting.

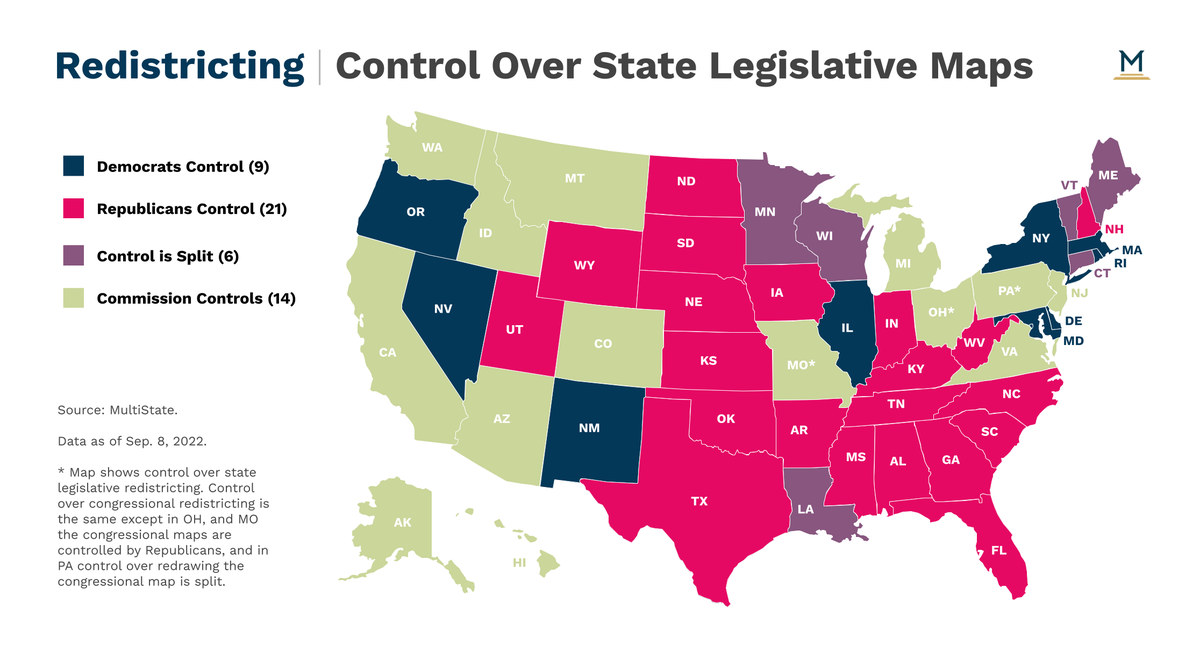

Although there are some federal statutory and constitutional limitations, for the most part, states determine their own redistricting methods. Some states prohibit redistricting to take place more than once during a decennial census period, but litigation around state-drawn maps has proliferated and state legislative and congressional districts have been redrawn by courts or judges have ordered states to do so after the initial maps were enacted. Nonetheless, political norms and state statutory and constitutional limits have restricted the use of mid-decade redistricting to an extremely rare event over the past 100 years of American history. In fact, the biggest trend in redistricting this century is actually taking the power of drawing maps away from state lawmakers and placing it in the hands of independent or bipartisan commissions.

The most famous recent case of mid-decade redistricting sounds awfully familiar. It took place in Texas in 2003. During the 2001 legislative session, the Texas Legislature was split between a Republican Senate and a Democratic House. The two chambers failed to come to an agreement on new maps after the 2000 census, which forced the courts to draw the congressional districts in Texas for the 2000s. But after the 2002 elections, Republicans gained a majority in the Texas House and thus controlled the entire legislature when lawmakers returned to Austin in 2003. U.S. House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-TX) encouraged lawmakers in his home state to pass a new redistricting plan, telling the press that, “I'm the Majority Leader, and we want more seats.” Democrats in the Texas House responded by leaving the state and denying the legislature the quorum needed to move legislation.

Congressman DeLay's office sought assistance from the Department of Homeland Security and other federal agencies to track down the missing Democrats, and state officials threatened them with fines. Ultimately, Gov. Rick Perry (R) called a special legislative session to pass the redistricting plan, and enough Democrats returned to reestablish the quorum. But the plan’s troubles shifted to the Senate, where senators cited a traditional “two-thirds rule” requiring supermajority approval to move a measure to a floor vote. After initially pledging to uphold that tradition, the powerful Lt. Governor Dewhurst (R) announced an exception to the two-thirds rule for congressional redistricting measures after he realized he could not convince the needed two Democratic senators to vote for the plan. This rule reversal itself resulted in senators temporarily leaving the state in protest and denying a quorum in the Senate. Finally, during a third special legislative session in September, the new maps were enacted on a party-line vote.

The redistricting shifted the Texas representation in the U.S. House by 6 seats from a Democratic majority of 17 of 32 seats in 2003 to a Republican majority of 21 of 32 seats in 2005.

Texas wasn’t alone in the 2000s-era mid-decade redistricting. Republicans in Colorado enacted new congressional districts in 2003 after flipping political control of the state legislature, similar to Texas. However, the Colorado Supreme Court invalidated the congressional maps, ruling that the state constitution only allows for one redistricting plan per decade. Georgia lawmakers also enacted new maps in 2005 after Republicans captured control of both chambers of the state legislature in the 2004 elections.

These efforts at mid-decade redistricting during the oughts sparked fear that states were reverting back to the 19th-century norm of redistricting every time a state changed political control. And while we didn’t see this continue during the 2010s redistricting cycle, today’s mid-decade redistricting efforts should renew those fears. Last week, when asked about the mid-decade redistricting taking place in other states, Utah Gov. Spencer Cox (R) warned that “Sometimes, I think we make changes to long-standing norms and policies, not realizing the consequences of those changes to those norms and policies. I fear that this may be one of those.”

This article appeared in our Morning MultiState newsletter on August 26, 2025. For more timely insights like this, be sure to sign up for our Morning MultiState weekly morning tipsheet. We created Morning MultiState with state government affairs professionals in mind — sign up to receive the latest from our experts in your inbox every Tuesday morning. Click here to sign up.

December 10, 2025 | Bill Kramer

-238a17-400px.jpg)

December 10, 2025 | Bill Kramer

November 5, 2025 | Bill Kramer